“What does peace look like when rivals share a table but not trust?”

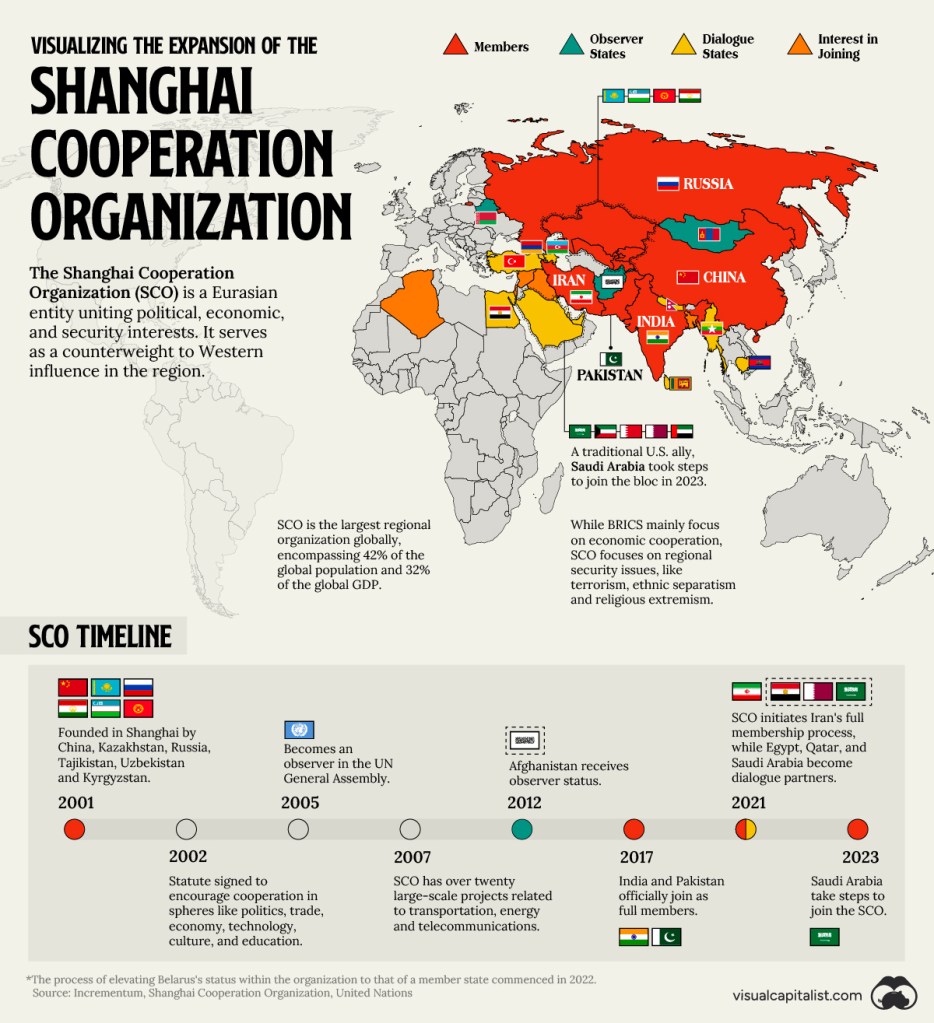

If you trace your finger across a map of Asia, you’ll find a vast, often volatile corridor—stretching from the steppes of Central Asia to the Himalayan borders, from the Caspian Sea to the Chinese heartland. It’s a region heavy with history, rich in resources, and riddled with tension. And yet, quietly threading through this geopolitical maze is a security alliance that few outside the region truly understand: the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

A Club of Rivals, Bound by Necessity

Founded in 2001, the SCO is no ordinary alliance. Its members include China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Iran, and four Central Asian nations—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Together, they represent nearly half the world’s population and a significant share of global GDP. But what makes the SCO remarkable isn’t its size—it’s its composition.

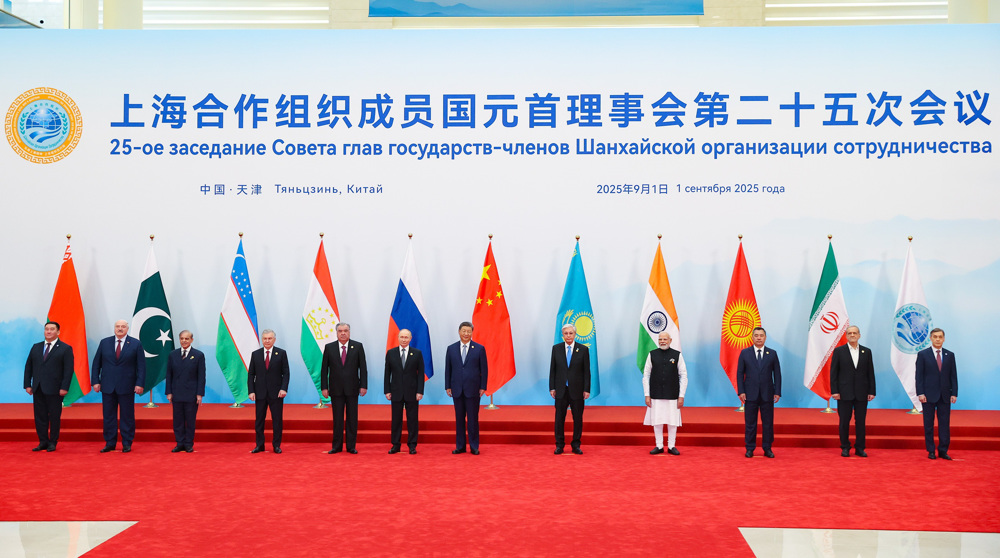

This is a club of rivals. Nuclear powers with unresolved border disputes. Nations with competing visions of regional leadership. Yet they meet, year after year, not to harmonize ideologies, but to confront shared threats. The SCO is a masterclass in pragmatic diplomacy.

The “Three Evils” and the Machinery of Cooperation

From its inception, the SCO has focused on combating what it calls the “three evils”: terrorism, extremism, and separatism. These aren’t abstract concerns—they’re lived realities, especially for Central Asian states bordering Afghanistan and other flashpoints.

To operationalize this mission, the SCO created the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS). Despite its unfortunate acronym, RATS is a linchpin of regional security. It facilitates intelligence sharing, maintains databases of suspected militants, and coordinates joint military exercises like the “Peace Mission” series. These drills aren’t just symbolic—they ensure that a Kazakhstani officer and a Russian commander can respond in sync when crisis strikes.

Afghanistan: A Test of Regional Resolve

The SCO’s relevance surged after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. As the Taliban regained control, neighboring countries braced for fallout—refugee flows, drug trafficking, and the resurgence of militant networks.

For Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, the threat was immediate. The SCO stepped in—not with sweeping declarations, but with quiet coordination. It became the primary platform for regional dialogue with the Taliban, prioritizing stability over ideology. Unlike Western-led efforts, the SCO’s approach is rooted in proximity, pragmatism, and shared vulnerability.

Dialogue in the Midst of Disputes

Perhaps the SCO’s most astonishing feat is its ability to host adversaries at the same table. India and Pakistan. China and India. These are not easy pairings. Yet the SCO doesn’t aim to resolve their bilateral tensions—it simply insists they keep talking.

By narrowing its focus to common threats—cross-border terrorism, narcotics, and regional instability—the SCO creates space for cooperation without demanding consensus. It’s diplomacy by compartmentalization. And in a world increasingly fractured by ideology, that’s no small achievement.

Not NATO, Not Neutral—But Necessary

SCO Summit 2025 in tianjin: Asia’s Push for a New Global Order

The SCO isn’t sleek. It’s not unified. It’s messy, often opaque, and shaped by the competing interests of its heavyweight members. But it works. In the heart of Eurasia, where instability threatens to spill across borders, the SCO offers a framework for dialogue, deterrence, and cautious collaboration.

In a time when global alliances are fraying and polarization is rising, the SCO reminds us that peace doesn’t always come from perfect alignment. Sometimes, it emerges from shared necessity—and the quiet courage to cooperate with those we mistrust.

“In a world of shifting loyalties, perhaps peace begins not with unity, but with the courage to keep showing up.”

#SCO(ShanghaiCoorperation Organisation) #EurosianDiplomacy #TianjinSCOSummit2025 #Peacebuilding #Dialogue

Leave a comment