In the complex tapestry of 21st-century geopolitics, the Indonesian island of Kalimantan is quietly emerging as a focal point, its strategic significance amplified by shifts in global power dynamics, particularly China’s evolving demographic realities and its enduring maritime ambitions. This analysis delves into Kalimantan’s multidimensional role, moving beyond conventional military perspectives to explore the subtle yet profound contest for human capital and influence south of the South China Sea.

1. China Demographic Decline : The unfolding crisis behind the strategic shift

The demographic transformation underway in China represents one of the most profound challenges to its long-term trajectory. Once the world’s most populous nation, China is now confronting an unprecedented and largely irreversible population decline. The National Bureau of Statistics of China reported a population decrease of approximately 2.08 million people in 2023, marking the second consecutive year of decline. This trend is projected to accelerate dramatically; the United Nations’ 2022 World Population Prospects report forecasts China’s population could shrink to 1.31 billion by 2050 and potentially fall below 800 million by 2100 under medium-fertility scenarios.

More critically, the working-age population (15-64 years) is expected to decline by over 200 million by mid-century, from roughly 980 million in 2020 to around 760 million by 2050. This demographic contraction has stark implications: a rapidly aging society with a burgeoning dependency ratio, escalating labor costs, and immense pressure on social welfare systems, healthcare, and even military recruitment.

China’s total fertility rate, estimated at a mere 1.09 births per woman in 2022 by the National Health Commission, is significantly below the 2.1 replacement rate, indicating a systemic demographic imbalance that policy adjustments are unlikely to reverse in the short to medium term. This demographic weakening directly erodes the foundation of China’s past economic growth—cheap, abundant labor—and necessitates a strategic reorientation in how it sustains its influence and economic vitality abroad.

2. Why the South China Sea Matter More than Military Posture

While often framed through the prism of military posturing and sovereignty disputes, the South China Sea’s true strategic importance to China extends far beyond territorial claims. It serves as a vital maritime artery for global trade and energy, with an estimated one-third of global maritime trade, valued at over $5 trillion annually, transiting its waters. Crucially, over 80% of China’s oil imports and a significant portion of its raw material and finished goods exports pass through this sea.

For Beijing, the South China Sea is not merely a shipping lane but a critical corridor for power projection, extending its reach towards Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and eventually East Africa, underpinning its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China’s extensive investments in artificial islands, dual-use facilities, and advanced radar systems across the Spratly and Paracel Islands are designed not only to assert territorial control but also to ensure uninterrupted access and operational continuity across this maritime expanse during peacike the Makassar Strait and the Celebes Sea—is paramount for extending this influence further south. This is precisely where Kalimantan’s geopolitical significance comes into sharp focus.

3. Kalimantan: The Human Resource Hinterland South of the Strategic Line

Kalimantan, the Indonesian portion of Borneo, is not directly embroiled in the South China Sea territorial disputes. However, its immediate proximity to these contested waters and its strategic position between the South China Sea and the Java Sea make it a pivotal location for logistical staging, maritime connectivity, and future economic development.

Demographically, Kalimantan is a dynamic region. According to Indonesia’s Central Statistics Agency (BPS), the island is home to over 16.6 million people as of 2023, with several provinces exhibiting population growth rates above the national average. East Kalimantan, for instance, recorded a growth rate of 3.2% in 2022. Crucially, Kalimantan boasts a significantly younger demographic profile, with a median age of approximately 29.5 years, nearly a decade younger than China’s median age of around 38.8 years.

Provinces like East Kalimantan, North Kalimantan, and Central Kalimantan possess young, increasingly urbanized populations that represent a substantial long-term labor reserve for regional and potentially international supply chains. Unlike the densely populated and politically centralized island of Java, Kalimantan remains comparatively under-urbanized and fragmented, presenting both unique opportunities for development and potential vulnerabilities to external influence.

4. A Fragmented Governance Landscape: An Opportunity for Quiet Influence

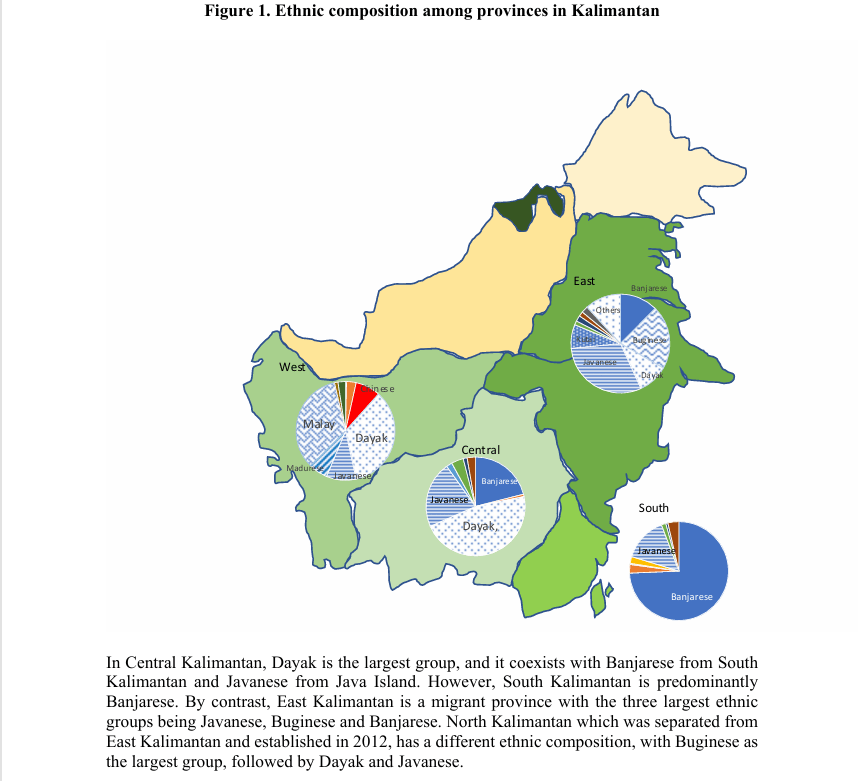

A critical, yet often overlooked, aspect of Kalimantan’s internal political geography is its decentralized and fragmented subnational governance structure. The island is divided into five provinces, each with autonomous local governments, elected governors, and regional legislatures, possessing varying administrative capacities and regulatory frameworks. While decentralization has fostered local development initiatives, it has also led to uneven development, inconsistent regulatory oversight, and increased susceptibility to external pressures, particularly in resource-rich areas.

China has historically demonstrated a strategic adeptness in navigating such fragmented environments. Across parts of Africa, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private firms have cultivated direct relationships with local elites and provincial officials, often circumventing central government scrutiny.

China’s Foreign Policy 2024: Strategic assertiveness and diplomatic adaptation

For example, in Laos and Cambodia, Chinese companies have secured vast land concessions and resource extraction rights through direct negotiations with provincial authorities. Similar dynamics are emerging in Kalimantan: local leaders, eager for infrastructure development and foreign investment, may readily invite Chinese capital. Weak environmental and labor regulations at the subnational level could facilitate the establishment of long-term economic footprints in critical sectors such as logistics, port operations, mining, and vocational training. While ostensibly commercial, these engagements can subtly accumulate into strategic leverage, especially if local labor, transport networks, and digital infrastructure become increasingly reliant on Chinese financing, platforms, or technology.

5. Indonesia’s Capital Relocation to Kalimantan: Strategic Gamble or Opportunity

President Joko Widodo’s ambitious decision to relocate Indonesia’s capital from Jakarta to Nusantara, a planned smart city in East Kalimantan, profoundly elevates the island’s strategic importance. The relocation, enshrined in law in 2022, aims to alleviate Jakarta’s severe environmental and population pressures while promoting more equitable development across the Indonesian archipelago.

This move creates a new national center of gravity in a region already attracting significant international attention. Nusantara is projected to require hundreds of billions of dollars in infrastructure investment—including roads, housing, energy grids, and advanced digital systems. As Indonesia’s largest trade partner and a significant infrastructure financier through the BRI, China has expressed considerable interest in contributing to this monumental project. While Indonesia has emphasized a preference for diverse international partners, including Japan, South Korea, and the UAE, the sheer scale of the project and China’s financial capacity mean that Chinese firms could become central players in the very region Indonesia is developing as its administrative and symbolic core. The long-term implications are significant: Nusantara could serve as a crucial test case for Indonesia’s ability to balance its development needs with the imperative of strategic autonomy, determining whether Kalimantan emerges as a platform for robust Indonesian leadership in Southeast Asia or becomes another theater for the soft extension of Chinese influence.

6. China’s Broader Interest in Demographics and Labor Beyond Its Borders

China’s engagement with Southeast Asia is evolving beyond its traditional focus on energy resources, mineral extraction, and large-scale infrastructure projects. Increasingly, access to and development of foreign labor and human capital are becoming core strategic objectives. As the Chinese domestic workforce contracts and labor costs rise, the imperative to cultivate overseas labor corridors will intensify.

This trend is already evident. Chinese firms operating along the China-Laos Railway corridor and within Special Economic Zones in Cambodia and Myanmar are actively developing vocational training programs for local workers to support Chinese-funded industrial parks and agricultural ventures. This model is highly likely to be replicated in Kalimantan. The establishment of vocational training centers, university exchange programs, and even formal labor migration agreements could quietly integrate Kalimantan’s youthful population into regional supply chains increasingly shaped by Chinese capital and standards. While offering immediate benefits such as jobs, skills transfer, and investment, such models could also subtly anchor Kalimantan to a strategic orbit not solely defined by Jakarta’s national interests.

7. Maritime Implications: The View from Makassar and Beyond

From a maritime security and strategic perspective, Kalimantan’s extensive coastline borders the Makassar Strait, a critical deep-water channel that serves as an alternative to the Malacca Strait for linking the Pacific and Indian Oceans. This strait is particularly vital for large vessels, including supertankers and submarines, that cannot easily navigate the shallower Malacca Strait. Control or significant influence over infrastructure along this corridor—including major ports like Balikpapan and Tarakan, fuel depots, and crucial digital cable landing stations—would provide China with a strategic redundancy route for its maritime trade and naval movements in the event of disruptions in the Malacca Strait or the northern South China Sea.

Furthermore, if Chinese firms play a substantial role in developing Kalimantan’s port cities, such as Balikpapan, Tarakan, and Pontianak, into advanced transshipment hubs, Beijing’s broader maritime strategy will gain significant depth beyond its overt military footprint. These projects, while civilian in nature, possess inherent dual-use potential and long-term strategic utility, enhancing China’s logistical reach and maritime domain awareness in a critical geopolitical space.

8. Competing Interests: Kalimantan Is Not China’s for the Taking

It is crucial to acknowledge that Kalimantan is not a passive recipient of external influence. Local communities, indigenous groups, and national civil society organizations are increasingly vocal in pushing back against environmentally destructive development projects and perceived foreign overreach. Notable

examples include protests against coal mining expansions and palm oil plantations that have led to land disputes and ecological damage. Indonesia itself, as a G20 economy and an influential member of ASEAN, maintains robust diplomatic and economic relationships with a diverse array of global powers, including Japan, South Korea, the United States, Australia, and increasingly, the Gulf states. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, for instance, have committed significant investments to Nusantara and other infrastructure projects across Indonesia, signaling a diversification of partnerships.

In this intricate geopolitical landscape, Kalimantan is becoming a contested space of influence—not through direct military confrontation, but through the strategic deployment of infrastructure, labor agreements, educational initiatives, and capital flows. The decisions made by Indonesian policymakers and local stakeholders over the next decade—regarding who builds what, where, and for whom—will profoundly shape the strategic alignment and future trajectory of this critical region for generations to come.

Conclusion: Kalimantan and the New Geopolitics of Demographics

As the Indo-Pacific region undergoes a profound realignment driven by great power competition, the escalating impacts of climate change, and unprecedented demographic transitions, Kalimantan finds itself unexpectedly at the strategic nexus. China’s accelerating demographic decline compels it to look outward for sustained access to labor, natural resources, and enhanced strategic depth. Kalimantan, with its youthful population, advantageous geography, and complex governance landscape, presents a compelling combination of all three.

However, this future is far from predetermined. If Indonesia strategically asserts its national vision for equitable development, strengthens its governance frameworks, actively diversifies its international partnerships, and genuinely empowers its local populations, Kalimantan can emerge not as a demographic solution for China, but as a resilient and dynamic strategic cornerstone for Southeast Asia. In a world where geopolitical contests are increasingly waged through flows of data, people, and capital, Kalimantan’s enduring value transcends its natural resources; it lies fundamentally in who inhabits its lands, who governs its future, and who ultimately shapes its destiny.

Leave a comment